In this chapter, I want to share the reasons for my fascination with the dan bau, as well as how I compose for it. Paradoxically maybe, my connection with the dan bau grew stronger the longer I spent away from Vietnam. I believe it serves me as a link to my Vietnamese culture, especially since I made the decision to stay abroad. It’s a way for me to bring a piece of my culture with me and to make my mark in the music world. Through my works, I want to showcase the incredible versatility of the dan bau in various musical contexts, ranging from traditional solo performances to experimental pop styles, but also to expand the expressive possibilities of the instrument through the discovery and mastering of new extended playing techniques.

Through my own practice, both as a composer and as a performer, I have discovered several new extended techniques, some of which I can shortly demonstrate here (more detailed videos and explanations will follow in my later papers):

Video 1: Playing dan bau with two glasses to create multiphonic sounds

Video 2: Playing dan bau with a bow

Video 3: Playing dan bau with a glass

Video 4: Playing the dan bau by plucking the strings with the fingers

Video 5: Playing dan bau with e-bow

Video 6: Playing dan bau with a comb

Video 7: Playing dan bau with a bag-sealing clip to produce a gong sound

5.1 Compositions

My compositions often deal with questions such as: What is happening to me in this period? Which issues I am currently busy with in my life? What are my concerns with society, how it affects me, or what can I do about that? Or sometimes it could be as basic as the simple joy of discovery – what could be my challenge for today? I’m using the dan bau as a tool in my composition to express all that. The form and the instrumentation of the piece reflect my concepts, and are sometimes influenced by the constraints placed by whoever commissioned the piece.

Undulation (for dan bau), 2018

My pieces for dan bau solo emphasize the raw organic beauty of dan bau’s sound. Without any electronic manipulations or additional effects the instrument takes the center stage, showcasing its remarkable expressive capabilities and ability to captivate listeners through its pure tones. This piece is a mix of sorts between traditional and contemporary music. I composed it in 2018 when I just moved to Hamburg and had strong feelings of nostalgia for Vietnam, filled with the memories of riding a motorbike on the bad road, in a place where I often was. My astrological sign in the Lunar calendar is horse, so I used the toy horses as a representation of myself during this piece. The piece was premiered at a New Music Festival organized by Prof. Hermut Erdmann in 2018; Hanoi City Blues concert at the University of Bonn in 2019; Tohuwabohu #7 concert – part of Blurred edges Festival für aktuelle Musik in Hamburg in 2019.

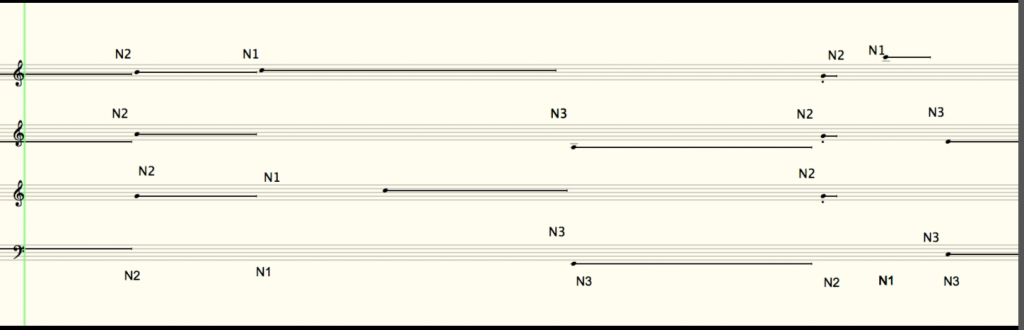

Untitled (for dan bau and electronics), 2021

Oblivion (for trio dan bau, saxophones, accordion and video), 2020

Dan bau in pop experimental style, 2020

5.2 Dan bau in improvisation

Similarly to traditional music anywhere in the world, Vietnamese traditional music is also rooted in improvisation. Music notation appeared quite late and the main way of learning was through oral tradition, where the student would carefully listen and observe the master, and try to catch all the nuances with no written instructions. Basic structure of any individual piece would be more or less stable, but allowed for a large amount of improvised input, and that was, in turn, the main way a performer would demonstrate their creativity and virtuosity. Style, based on the geographical area where it originated, defined a set of rules and constraints in which the improvisation operated, for example ”every C note has to be played vibrato”, and many others. While moving in that space, the players could add new notes, speed up or slow down, and add their own special touches. Whether playing alone or with others, the music was never exactly the same twice. The artists had the freedom to express themselves in their own unique way. Nowadays, we do use Western notation and music sheets for our traditional music, but the notated material is just a part of what is expected to sound – similar to lead sheets in jazz music, it provides a frame within which the instrumentalists are free to improvise, following, of course, the rules of the specific style. Unlike jazz, our traditional music is based on melodies, rather than harmonies, and the melodies (or lyrics) are the basis for the form.

The mix of my experiences with traditional Vietnamese music (not just as a dan bau player, but as a singer and erhu player too) and with free improvisation (dan bau, piano, objects, electronic music) makes me a woman of two worlds – able to step into each of them, but also to thrive right on the border. I enjoy the fusion of different elements, and often draw inspiration for my art from both these worlds.

I first started to improvise with the dan bau in 2016, and have slowly been expanding, discovering and exploring different expressional potentials of the instrument ever since. I experimented with many different objects (hair combs, glasses, bow and e-bow, tuning fork, chopsticks, head massage spider, bag sealing clips, different other plastic materials, etc.), personally discovered new extended techniques (special tremoli; multiphonics on dan bau; deep vibrato; and many others), and perfected the traditional playing techniques – all in order to further develop my aesthetics and my instrumental skills, so I could better play both solo and in ensembles of different sizes.

The inspiration for some of the extended techniques I developed came from playing with other instrumentalists and observing how they play their instruments. To give one concrete example: I had the chance to play with a colleague of mine who is a cellist, and I was fascinated by the way she uses and controls her bow to shape the sound. I noticed that the angle of the bow in relation to the string plays a big role in the sound quality, which is also affected by the intensity of the pressure the bow exerts on the string. I applied the same to the dan bau, using the bow, and the results were amazing, allowing me to control the sound better. This elevated degree of control helped me further develop my personal way of playing. Still, I am sure that there are many other new and exciting extended techniques just around the corner, waiting to be discovered!

The dan bau, being a traditional Vietnamese instrument, brings with it many distinctive sound qualities, especially in the context of Western musical instruments. Improving it here in the West, I have learned a lot about how to balance tradition and new ways of producing sound to be able to communicate and interact with others. Dan bau has a limited dynamic range and control of the loudness, which is something to pay particular attention to when playing in a big group and/or playing with instruments with a bigger range of dynamics such as piano, accordion, saxophone, or others… I needed to think about how I could bring the voice of the instrument in balance with others. Some extended techniques are pretty quiet so I can use them at the moment when the music settles down and opens up a space for that. I often listen to the way the energy of the piece moves, letting me predict the likely outcomes – this in turn leads to the decisions to be in front, and lead; or to support others.

mīrārī duo

The group was founded in 2019. Mirari Project is a collaboration between me and composer and accordionist Goran Lazarevic. For the concert “On the other side of the reflection” at Blurred Edges Festival in 2019, our concept explored the meanings of reciprocity, feedback and reflection through the interplay of movement and sound. The timbres of dan bau, accordion and objects communicated with the existing environmental noises, blurring the lines between inside and outside. Instead of sitting and playing as tradition, I started from outside, on the street walking to the concert room, using the batteries and wearing the loudspeaker behind my back. I held the instrument with my left hand (s. picture below) and I played the long tones by plucking with my right hand. This concert was the first time I used dan bau multiphonics. It is the extended technique I discovered, performed by using 2 glasses, one glass is held with the right hand and is lightly touching the string, while the left hand is holding a second glass and is tapping the glass softly on the string. Moving the tapping glass left and right we invoke different overtones to sound simultaneously with the fundamental.

Photo by Gunnarlettow at Baustelle eins

Another activity of the mīrārī duo is working with dancers. We often participate in the “Improabend” events at Triade, led by Sigrid Bohlens, Natascha Golubtsova and Annett Walter. Triade, the venue where Improabend series takes place, is a unique experimental space for dance improvisation with live music, where we engage in dialogue between dance and music. How can dance and music inspire each other? How do sound and movement combine in space? How do special moments of encounter arise and where do joint processes develop in improvisation? How can a lot of space for resonance be created? What happens when the common focus is on pauses and listening?

The events usually have 10-15 participants. The close proximity of dancers and musicians, a pleasant wooden floor, sound space and stage lights create an intimate and intense atmosphere that invites people to meet each other. The character of an improvisation evening can vary between jam and performance. Each improvisation evening includes a guided warm-up, small improvisation tasks or improvisation scores, which can then lead into a longer, free improvisation. But how a process is concretely shaped in the interplay of musicians and dancers is a new, exciting experiment each time and open to all forms of expression.

We, the musicians, often have a discussion and create the text score together with the leader before each event. We try to make space for everyone who participates, so that they can express themselves individually, together with other dancers, or with the music. In terms of energy, we make different ranges of groups each time and have an open score where dancers can decide to act as an audience or to join the stage as dancers. While playing, we switch between different modi, some of which I will mention here:

- Follow the movements of a single dancer, or of a group

- Play as a duo, but purposefully ignore what the other musician is doing, and just focus on the dancer(s). Every dancer chooses freely which instrument they wish to interact with

- Play, and let the dancers follow the music

- Play a short (15-60 sec) improvisation, and have the dancer dance afterwards to the memory of it

To keep things interesting and fresh for the dancers we made different types of music: sometimes more in the direction of meditation, and minimal music, but other times with a lot of energy, changing quickly from the notes to the noises and from quiet to loud to create some challenging situations.

Photos from an improvisation with dancers from Triade

We didn’t want to leave the exploration of space only to the dancers, so we worked with the space too. We took different playing positions in the room, changed our facing during the performance, and I would often change the direction of my loudspeaker, all in order to produce different reverberations and sound reflections. To further explore the space, I would occasionally use objects and small, hand-held instruments, in addition to dan bau, so I could move around while playing and change the atmosphere even more. During the open score sections we’d often turn on the stage lights, and let color, light and shadow influence our performance.

Through the experience of participating in these Improabend events, we developed our perception of sound, movement and space. After every event, we’d sit together in a circle, musicians and dancers, and reflect on the performance we just did. We’d often mention how we are aware of being in the space, and how the dance and music share that same space. That kind of input and sharing helped me to develop my skills and influenced the way I play and think about music.

SPIIC ensemble

The futuristic-sounding acronym SPIIC stands for “Studio for Polystylistic Improvisation and Interdisciplinary Crossover”, which was formed as part of the Innovative Hochschule/Stage_2.0 project (more details about the SPIIC project can be found here). It’s led by the border-crosser Vlatko Kučan: improvisor, musician, and composer. SPIIC ensemble gathers students from different departments of the HfMT (multimedia composers, jazz instrumentalists, old music specialists, pianists, percussionists, violin players – to name but a few) and provides them with the platform, structure and guidance to search for common musical languages, perfect their capabilities of free musical communication, and enhance the understanding of their own instruments. I have been a member of the ensemble since 2019 and three aspects of its functioning have been particularly important for me: the size of the ensemble (usually 5 – 15 performers); opportunity to play with and learn from world-renowned improvisers (such as Fred Frith, Evan Parker and many others); and the fluidity of the ensembles instrumentation and player preferences and levels.

The Art of Improvisation – TAOI 2021/II Part 2

At its core, the SPIIC ensemble is a student ensemble, with a focus on learning and developing improvisational skills. This fact means that there is inherent instability in its membership which allowed me to experience using dan bau in a wide range of different configurations. Some of the challenges evident in playing in smaller, fixed ensembles (such as mīrārī duo or Bunte Luft trio) are exacerbated in a larger ensemble. I refer here specifically to the volume, balance between the instruments, and the usage of musical space. To deal with these challenges I had to work not only on my instrumental skills but also, and maybe more importantly, on my listening skills. My sensibilities improved so I could listen better to all of my co-players, and also feel and sense myself, so I can better judge which input from my side the music needs. I discovered, developed and perfected many extended techniques of playing, all to increase the expressional capabilities of my instrument.

When I first started playing with the SPIIC ensemble, my mind was a whirlwind of activities, questions and doubts: Is the music I play interesting? Am I good enough? How is my technique? Does the music we make together nice for the audience? …and many others. Now, 4 years later, I am able to just relax and enjoy. I am no longer worried if I did good – playing in SPIIC has made me more confident, helped me develop, and made me a better listener. I see many reasons for why it was such an important factor to my work both as a composer and an improviser and here I will mention the most important ones. Concerts – we played in many different places (concert halls, open spaces, construction sites, galleries, “black boxes”…). Space shapes the sound and atmosphere is an additional influence in how we play, which all brings new ideas and experiences. Lecture/performances – the guests Vlatko Kucan invited are the highest calibre improvisers in the world, and the format of the lecture/performance allowed us not only to listen to them, play with them, but also to hear them speak, explain their own individual approaches to music and improvisation, and to go into a dialogue with them. These in-depth discussions have had a big impact on me and have helped me overcome the concerns I’ve previously mentioned. Rehearsals – embracing both the free improvisation as well as the idiosyncrasies rooted in backgrounds, affinities and specialization of individual players was only possible through masterful and thoughtful guidance by Vlatko Kucan, who structured our rehearsals with the plethora of interesting and helpful exercises, and often reminded us that pauses are also a part of music.

Some photos of SPIIC ensemble

All of this made me think deeper about the relationships between tradition and improvisation, and the different aesthetics governing jazz improvisation, free improvisation, traditional improvisation, and world music. I strive to preserve some of the distinctive elements characteristic of me and my culture and to incorporate them into the improvisation, to extend its language and not be limited by style.